‘Wait-and-See Pudding with Patience Sauce’

2017- Royal Photographic Society International Photography Exhibition 162

- Photo Vogue Festival 2019

- Prints for Refugees

- Creative Review Photography Annual 2017

- Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize - National Portrait Gallery 2017

Catherine Hyland’s portraits from the Caribbean island of Nevis are very simple. The first shows a man standing in front of a timber house holding a petrol-powered strimmer. He’s wearing grey work-clothes to protect him from the flying grass, a rough-cut plastic apron covering his waist and thighs, shinguards and workboots protecting his feet and legs. This is a picture of a man who labours. Go forward a few pages and there is another portrait striking in its simplicity, another picture of a man who labours. This shows a man standing in the island’s hot Springs. The man is wearing only shorts. He’s well built in a muscular and well-fed sense, his face has an expression of weariness, his arms are smeared in white clay, perhaps from the springs.

These are not idyllic springs. They’re a muddy trickle streaming through a manmade culvert, with pipes by one side indicating that the springs are going to be ‘developed’, the grass concreted over to make for a less muddy experience. So two simple pictures, but containing a wealth of detail that encapsulates the contemporary issues that are embedded in the portraits that Hyland has made. These people are not just portrayed in isolation then, but are set into the land on which they live. And they do live on the land. Though tourism is now the main industry on Nevis (and high-end tourism at that), subsistence farming is still the livelihood for many people.

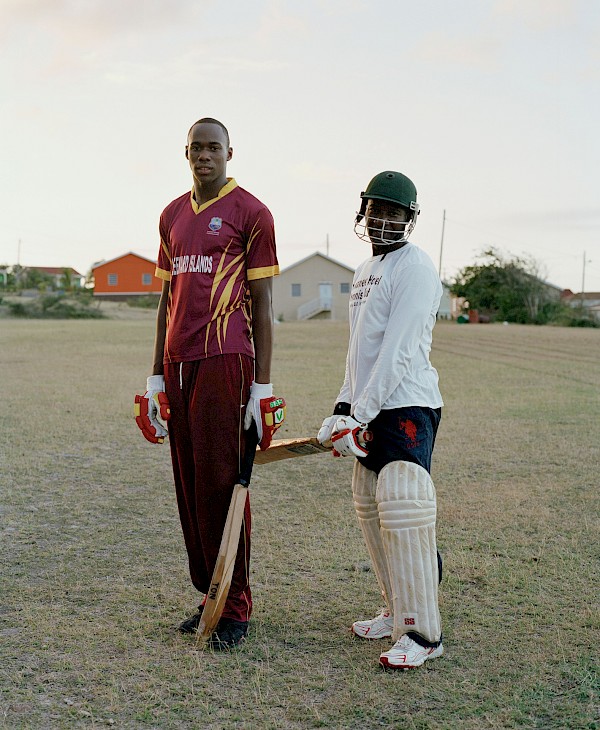

This is the world that Hyland captures, a world of semi-rural settlements that date back to the slave villages that dotted the island when it was an island of sugar plantations and slaveholdings. There are portraits made by ramshackle homes and fields of crops, the fertility of the island evident in the greenery that surrounds every spot. But there is also contemporary life. Hyland’s portrait of the young girl in shorts and knee high socks looking into the camera speaks of a more modern life, a modernity amplified by the giant speaker lodged in the picture right of frame. Most interestingly, modernity is also evident in the first two pictures mentioned. While one references the use of carbon fuels, the other points to the geothermal energy that exists beneath the surface of the island.

Nevis is trying to become the world’s first carbon-neutral island. The key to this is exploiting the geothermal reserves that lie beneath those hot springs and in the process overcoming the island’s dependency on expensive diesel-fuelled generators. The idea is that then the island will be able to sell power to other islands and develop an economy through industry and technology.

Unfortunately, the actual drilling and installing a geothermal electricity generation plant is proving more difficult than the rhetoric would allow. So instead of seeing a 21st century island (which doesn’t exist yet) heading the world’s greenest island lists, we have a place where the springs are used by locals as a place to unwind and relax at the end of the day.

This is the real world at odds with the realities of economic development and Hyland shows this with portraits that are far more complex than they appear at first sight. In this regard, they share commonalities with her landscape projects Universal Experience and Belvedere. In these Hyland merged the geological and environmental realities of the harsh landscapes of Western China with human attempts to tame them.

In Nevis, Hyland has done something similar. Here land is everything and it infuses the lives of the villagers she photographs. Landscape on Nevis is, quite literally power and it is evident both in the natural, the domestic and the personal environments that she photographs. These portraits point to a world we try to contain and control, but somehow it is always beyond our grasp. We don’t control land, land controls us. So instead of the rhetoric of economic growth and development, Hyland gives us real people living real lives on a real island. Nevis is not the greenest island on earth, it’s not a paradise, it’s not even idyllic. It is simply human and all the more beautiful because of it.

Installation